Danh ngôn

“Thế giới này, như nó đang được tạo ra, là không chịu đựng nổi. Nên tôi cần có mặt trăng, tôi cần niềm hạnh phúc hoặc cần sự bất tử, tôi cần điều gì đó có thể là điên rồ nhưng không phải của thế giới này.”

“Ce monde, tel qu’il est fait, n’est pas supportable. J’ai donc besoin de la lune, ou du bonheur, ou de l’immortalité, de quelque chose qui ne soit dement peut-etre, mais qui ne soit pas de ce monde.”

(Albert Camus, Caligula)

.

“Tất cả chúng ta, để có thể sống được với thực tại, đều buộc phải nuôi dưỡng trong mình đôi chút điên rồ.”

“Nous sommes tous obligés, pour rendre la realite supportable, d’entretenir en nous quelques petites folies.”

(Marcel Proust, À l’ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs)

.

“Nghệ thuật và không gì ngoài nghệ thuật, chúng ta có nghệ thuật để không chết vì sự thật.”

“L’art et rien que l’art, nous avons l’art pour ne point mourir de la vérité.” (Friedrich Nietzsche, Le Crépuscule des Idoles)

.

“Mạng xã hội đã trao quyền phát ngôn cho những đạo quân ngu dốt, những kẻ trước đây chỉ tán dóc trong các quán bar sau khi uống rượu mà không gây hại gì cho cộng đồng. Trước đây người ta bảo bọn họ im miệng ngay. Ngày nay họ có quyền phát ngôn như một người đoạt giải Nobel. Đây chính là sự xâm lăng của những kẻ ngu dốt.”

“Social media danno diritto di parola a legioni di imbecilli che prima parlavano solo al bar dopo un bicchiere di vino, senza danneggiare la collettività. Venivano subito messi a tacere, mentre ora hanno lo stesso diritto di parola di un Premio Nobel. È l’invasione degli imbecilli.”

(Umberto Eco, trích từ bài phỏng vấn thực hiện tại Đại học Turin (Ý), ngày 10 tháng 6 năm 2015, ngay sau khi U. Eco nhận học vị Tiến sĩ danh dự ngành Truyền thông và Văn hoá truyền thông đại chúng. Nguyên văn tiếng Ý đăng trên báo La Stampa 11.06.2015)

Ban Biên tập

Địa chỉ liên lạc:

1. Thơ

tho.vanviet.vd@gmail.com

2. Văn

vanviet.van14@gmail.com

3. Nghiên cứu Phê Bình

vanviet.ncpb@gmail.com

4. Vấn đề hôm nay

vanviet.vdhn1@gmail.com

5. Thư bạn đọc

vanviet.tbd14@gmail.com

6. Tư liệu

vanviet.tulieu@gmail.com

7. Văn học Miền Nam 54-75

vanhocmiennam5475@gmail.com

Tra cứu theo tên tác giả

- A. A. Fadeev

- A. Puskin

- A. T.

- Abdulrazak Gurnah

- Abraham F. Lowenthal

- Ace Le

- Ace Lê

- Adam Gopnik

- Adonis

- Adrian Horton

- Agi Mishol

- Ái Điểu

- Ajar

- Akiko Miki

- Alain Guillemin

- Alan Phan

- Alăng Văn Gáo

- Alăng Văn Giáo

- Albert Camus

- Aldous Huxley

- Aleksandr Griboedov

- Alesandr Blok

- Alex Marshall

- Alex Smith

- Alex Thai

- Alex-Thái Đình Võ

- Alexander Fadeev

- Alexander Solzhenitsyn

- Alexandra Alter

- Alexandre FERON

- Alice Munro

- Alina Lesik

- Alison Flood

- Allen Ginsberg

- Amanda Gorman

- Amartya Sen

- Amelia Glaser

- Amos Oz

- An Nam

- Anatole France

- Anatoly Gavrilov

- Anders Olsson

- André Breton

- André Menras

- André Menras – Hồ Cương Quyết

- André Menras Hồ Cương Quyết

- Andrea Hoa Pham

- Andrea Kendall-Taylor

- Andreas Fulda

- Andreas Wimmer

- Andrew Postman

- Andy Cao

- Anh Anh

- Anh Hồng

- Anh Hồng (nhà thơ)

- Ánh Liên

- Anh Nhi

- Anh Văn

- Anika Zeller

- Anna Akhmatova

- Anna Maria Bracale Ceruti

- Anna Mitchell

- Anna Schmid

- Anne Carson

- Anne Cazaubon

- Anne Hébert

- Anne Henochowicz

- Anne Nguyễn

- Annie Ernaux

- António Jacinto

- Antôn Nguyễn Trường Thăng

- Archimedes L.A. Patti

- Arlette Quỳnh Anh Trần

- Arnold Schwarzenegger

- Artem Sakharov

- Arthur Koestler

- Arty Abel

- Arvind Subramanian

- Augustina

- Aurélie Coulon

- Aurelien Breeden

- Ba Sàm

- Bá Thụ Đàm

- Bạch Cúc

- Bạch Hoàn

- Bách Mỵ

- Bách Thân

- Bạch X. Phẻ

- Bạch Xuân Phẻ

- Bakhtin

- Ban Mai

- Bàn Văn Thòn

- Ban Vận động Văn đoàn Độc lập Việt Nam

- Bảo Chân

- Bảo Huân

- Bảo La

- Bảo Nhi Lê

- Bảo Ninh

- Bảo Phác

- Bảo Tích

- Bão Vũ

- Bảo Yến

- Barbara Demick

- Bashô

- Bạt Xứ

- Batrioldman

- Bauxite Việt Nam

- Bắc Đảo

- Bắc Phong

- Bằng Việt

- BB Ngô

- Bei Dao

- Benjamin Péret

- Benjamin Ramm

- Bertolt Brecht

- Bertrand Russell

- Bettina Rheims

- Bích Ngân

- Biếm họa

- Biên Cương

- Biệt Hiệu

- Bilahari Kausikan

- Bill Hayton

- Billy Collins

- Bình Nguyên Lộc

- Brahma Chellaney

- Branko Milanovic

- Brett Reilly

- Brian Pascus

- Brian Wu

- Brice Pedroletti

- Brodsky

- Bryan

- Bùi An

- Bùi Bảo Trúc

- Bùi Bắc

- Bùi Bích Hà

- Bùi Chát

- Bùi Chí Trung

- Bùi Chí Vinh

- Bùi Công Thuấn

- Bùi Công Trực

- Bùi Đức Lại

- Bùi Giáng

- Bùi Hải Quảng

- Bùi Hoàng Tám

- Bùi Hoằng Vị

- Bùi Huệ Chi

- Bùi Huy

- Bui Huy Hoi Bui

- Bùi Mai Hạnh

- Bùi Mạnh Hùng

- Bùi Mẫn Hân

- Bùi Minh Quốc

- Bùi Ngọc Tấn

- Bùi Quang Thắng

- Bùi Suối Hoa

- Bùi Thanh Hiếu

- Bùi Thanh Phương

- Bùi Thanh Tuấn

- Bùi Thụy Băng

- Bùi Tiến An

- Bùi Trân Phượng

- Bùi Trọng Hiền

- Bùi Văn Kha

- Bùi Văn Nam Sơn

- Bùi Việt Sỹ

- Bùi Vĩnh Phúc

- Bùi Xuân Bách

- Bùi Xuân Đính

- Bùi-Viết Văn Đức

- Bulgakov

- Bửu Chỉ

- C.D.

- Cái Lư Hương

- Cái Trọng Ty

- Cam Ly

- Cameron Shingleton

- Cảnh Chánh

- Cao Bảo Vân

- Cao Bình Minh

- Cao Chi

- Cao Gia An

- Cao Hành Kiện

- Cao Huy Thuần

- Cao Kim Ánh

- Cao La

- Cao Quang Nghiệp

- Cao Tần

- Cao Thị Hồng

- Cao Thu Cúc

- Cao Tự Thanh

- Cao Việt Dũng

- Cao Xuân Hạo

- Cao Xuân Huy

- Carl Bildt

- Carl O. Schuster

- Carlos Assunção

- Carolyn Mary Kleefeld

- Cát Linh

- Cẩm Tú

- Cấn Thị Thêu

- Chan Phuong

- Chanh Tam

- Charles Bo

- Charles Bukowski

- Charles S. Kraszewski

- Charles Simic

- ChatKP

- Chau Doan

- Châm Khanh

- Chân Minh

- Chân Pháp Xa

- Chân Phương

- Chân Xuân Tản Viên

- Châu Diên

- Châu Hải Đường

- Châu Hồng Thủy

- Châu Hữu Quang

- Chenn

- Chế Diễm Trâm

- Chế Lan Viên

- Chi Mai

- Chi Phương

- Chiêu Dương

- Chiêu Khiêm

- Chiharu Shiota

- Chim Hải

- Chim Trắng

- Chinh Ba

- Chính Tâm

- Chính Vĩ

- Chinua Achebe

- Chơn Không Cao Ngọc Phượng

- Christian Gampert

- Christian Welzel

- Christina Mary Hjortlund

- Christoph Giesen

- Christoph Sator

- Christopher Balding

- Christopher Goscha

- Christy Wampole

- Chu Dương

- Chu Hảo

- Chu Hoạch

- Chu Kim

- Chu Mộng Long

- Chu Quang Tiềm

- Chu Tử

- Chu Văn Lễ

- Chu Văn Sơn

- Chu Vĩnh Hải

- Chu Vương Miện

- Chu Xuân Diên

- Chung Le

- Claire Simon

- Clay Phạm

- Concepcion de Leon

- Connie Hoàng

- Cora Engelbrecht

- Costica Bradatan

- Cổ Ngư

- Công Nguyễn

- Cù An Hưng

- Cù Huy Hà Vũ

- Cù Mai Công

- Cù Tuấn

- Cung Minh Huân

- Cung Tích Biền

- Cung Trầm Tưởng

- Cư sĩ Minh Đạt

- D. S. Likhachev

- Da Màu

- Dạ Ngân

- Dạ Thảo Phương

- Dã Tượng

- DAD

- Dadolin Murak

- Damien Keown

- Dan Bilefsky

- Dan Slater

- Dana Gioia

- Danh ngôn

- Dani Rodrik

- Daniel Halpern

- Daniel Hautzinger

- Daron Accemoglu

- David Brown

- David Gascoyne

- David Marchese

- David Weinberger

- Ðặng Thơ Thơ

- Demetrio Paparoni

- DEUTSCHE WELLE

- Di

- Di Li

- Diêm Liên Khoa

- Diễm Thi

- Diễm Tường

- Diễn đàn Thế kỷ

- Diệp Duy Liêm

- Diệp Huy

- Ðinh Cường

- Dino Buzatti

- Dipanjan Roy Chaudhury

- Dmitri Prokofyev

- Dmitry Burago

- Dmitry Muratov

- Doãn Cẩm Liên

- Doãn Mạnh Dũng

- Doãn Mẫn

- Doãn Quốc Sỹ

- Dominique Lemieux

- Donald Inglehart

- Donna Ashworth

- Ðỗ Quang Nghĩa

- Ðỗ Quyên

- Du Tử Lê

- Dung Nguyễn

- Dũng Phan

- Dũng Trung Kqd

- Dũng Vũ

- Duy Lam

- Duy Tân

- Duy Thanh

- Duy Thông

- duyên

- Duyên Anh

- Duyên Khánh

- Dư Hoa

- Dư Kiệt

- Dư Thị Hoàn

- Dư Thu Vũ

- Dương Đại Triều Lâm

- Dương Đình Giao

- Dương Khánh Phương

- Dương Kiền

- Dương Ngạn

- Dương Nghiễm Mậu

- Dương Ngọc Thái

- Dương Như Nguyện

- Dương Phương Vinh

- Dương Thắng

- Dương Thiệu Tước

- Dương Thu Hương

- Dương Thuấn

- Dương Tú

- Dương Tường

- Dương Văn Ba

- Dương Vân

- Dylan Suher

- Đà Văn

- Đàm Hà Phú

- Đàm Hách Thành

- Đào An Khánh

- Đào Anh Kha

- Đào Công Tiến

- Đào Duy Anh

- Đào Hiếu

- Đào Lê Na

- Đào Ngọc Chương

- Đào Nguyên

- Đào Nguyễn

- Đào Nguyên Phương Thảo

- Đào Như

- Đào Phương Liên

- Đào Quang Toản

- Đào Tấn Phần

- Đào Thái Tôn

- Đào Thị Hương

- Đào Tiến Thi

- Đào Trung Đạo

- Đào Trường Phúc

- Đào Tuấn

- Đào Tuấn Ảnh

- Đào Văn Bình

- Đào Văn Thuỵ

- Đào Văn Tiến

- Đào Vũ Anh Hùng

- Đạt Nguyễn

- Đặng Anh Đào

- Đặng Bích Phượng

- Đặng Chương Ngạn

- Đặng Đình Cung

- Đặng Đình Mạnh

- Đặng Hà

- Đặng Hải Sơn

- Đặng Hoàng Giang

- Đặng Hồng Nam

- Đặng Hùng Võ

- Đặng Hương Giang

- Đặng Hữu

- Đặng Mai Lan

- Đặng Mậu Tựu

- Đăng Nguyên

- Đặng Phùng Quân

- Đặng Quốc Thông

- Đặng Sơn Duân

- Đặng Thái

- Đăng Thành

- Đặng Thân

- Đặng Thị Hảo

- Đặng Thơ Thơ

- Đặng Tiến

- Đặng Tiến (Thái Nguyên)

- Đặng Trung Nghĩa

- Đặng Túy

- Đặng Văn Dũng

- Đặng Văn Hùng

- Đặng Văn Ngữ

- Đặng Văn Sinh

- Đặng Vũ Vương

- Đặng Xuân Thảo

- Đặng Xuân Xuyến

- Đằng-Giao

- Điểm Thọ

- Đinh Bá Anh

- Đinh Cường

- Đinh Hoàng Thắng

- Đinh Hồng Phúc

- Đinh Hùng

- Đình Kính

- Đinh Lê Vũ

- Đinh Linh

- Đinh Ngọc Thu

- Đinh Phương

- Đinh Phương Thảo

- Đinh Quang Anh Thái

- Đinh Thanh Huyền

- Đinh Thị Như Thúy

- Đinh Trường Chinh

- Đinh Từ Bích Thuý

- Đinh Từ Bích Thúy

- Đinh Văn Đức

- Đinh Vũ Hoàng Nguyên

- Đinh Ý Nhi

- Đinh Yên Thảo

- Đoàn Ánh Thuận

- Đoàn Bảo Châu

- Đoàn Cầm Thi

- Đoàn Công Lê Huy

- Đoàn Hồng Lê

- Đoàn Huy Giao

- Đoàn Huyền

- Đoàn Khắc Xuyên

- Đoàn Lê Giang

- Đoàn Nhã Văn

- Đoàn Thanh Liêm

- Đoan Trang

- Đoàn Tùng Nguyễn

- Đoàn Tử Huyến

- Đoàn Việt Hùng

- Đoàn Xuân Kiên

- Đỗ Anh Hoa

- Đỗ Anh Tuấn

- Đỗ Bích Thuý

- Đỗ Cao Bảo

- Đỗ Duy Ngọc

- Đỗ Đức

- Đỗ Đức Đông Ngàn

- Đỗ Đức Hiểu

- Đỗ Hòa

- Đỗ Hoàng Diệu

- Đỗ Hồng Ngọc

- Đỗ Hồng Nhung

- Đỗ Hữu Chí

- Đỗ Kh

- Đỗ Kh.

- Đỗ Khiêm

- Đỗ Kim Thêm

- Đỗ Lai Thuý

- Đỗ Lai Thúy

- Đỗ Lê Anh Đào

- Đỗ Mạnh Hoàng

- Đỗ Minh Tuấn

- Đỗ Nghê

- Đỗ Ngọc

- Đỗ Ngọc Thống

- Đỗ Quang Nghĩa

- Đỗ Quang Vinh

- Đỗ Quý Toàn

- Đỗ Quyên

- Đỗ Quỳnh Dao

- Đỗ Thái Bình

- Đỗ Thắng Cảnh

- Đỗ Thị Thu Trà

- Đỗ Thiên Anh Tuấn

- Đỗ Trí Vương

- Đỗ Trọng Khơi

- Đỗ Trung Quân

- Đỗ Trường

- Đỗ Tuyết Khanh

- Đồng Chuông Tử

- Đông Hoài

- Đông Hồ

- Đông Kha

- Đông Ngàn Đỗ Đức

- Đông Nghi

- Đức Ban

- Đức Đàm

- Đức Flying Bay

- Đức Hoàng

- Đức Lê

- Đức Phổ

- Đức Tâm

- Đức Tiến

- E. M. Forster

- E.E. Cummings

- E.M. Chernoivanenko

- Eamonn Butler

- Eckart Kleßmann

- Eduardo Galeano

- Edward Hirsch

- Elena Pucillo Truong

- Elias Canetti

- Ellen Bass

- Eloisa Amezcua

- Emiel Roothooft

- Emma Loffhagen

- Emmanuelle Jardonnet

- Eric Henry

- Eric Weiner

- Erica Frantz

- Erik Harms

- Erik Korling

- Euan Ward

- Evgheni Dobrenko

- F.N.

- Federico García Lorca

- Feliks Kuznesov

- Filip Lech

- Flanny O’Connor

- Florence Noiville

- Florian Altenhöner

- Francis Fukuyama

- Francis Fukuyma

- François Guillemot

- Frank Dikötter

- Frank O'Hara

- Frankfurt

- Fred Hiatt

- Friedrich Dürrenmatt

- Friedrich Nietzsche

- Fritz J. Raddatz

- Gã Khờ

- Gabriel García Márquez

- Gabriel Josipovici

- Gaither Stewart

- Gaiutra Bahadur

- Gary Leupp

- Gặp gỡ và trò chuyện

- Georg Bönisch

- Georg Trakl

- George Burchett

- George Orwell

- George Perreault

- George Siemens

- Georges Condominas

- Gérard Noiriel

- Gerhard Will

- Germain Droogenbroodt

- Giang Dang

- Giang Lại Đức

- Giang Nam

- Giáng Vân

- Giao Nguyễn

- Giáp Văn Dương

- Gideon Rachman

- Giuse Lê Công Đức

- Goethe

- Gonçalo Fernandes

- Gottfried Benn

- Graham Allison

- Grigory Yudin

- Günter Kunert

- Gyảng Anh Iên

- Hà Duy Phương

- Hà Dương Tuấn

- Hà Dương Tường

- Hà Đình Nguyên

- Hạ Đình Nguyên

- Hà Huy Khoái

- Hà Huy Sơn

- Hà Hương

- Hà Lệ Minh

- Hà Ngọc Hòa

- Hạ Nguyên

- Hà Nguyên Du

- Hà Nhân

- Hà Nhật

- Hà Phạm Phú

- Hà Quang Vinh

- Hà Sĩ Phu

- Hà Thanh Vân

- Hà Thế

- Hà Thị Minh Đạo

- Hà Thúc Sinh

- Hà Thủy Nguyên

- Hà Tùng Long

- Hà Tùng Sơn

- Hà Văn Thịnh

- Hà Văn Thùy

- Hà Vũ Trọng

- Hagi Kenaan

- Hai An Vu

- Hải Hạc

- Hải Ngọc

- Hai Thanh

- Han Dang

- Hàn Giang

- Han Kang

- Hàn Vĩnh Diệp

- Hạnh Diễm

- Hạnh Nguyên

- Hạnh Phước

- Hạnh Viên

- Hannah Beech

- Hào Thiện Nhân

- Hari Kunzru

- Haruki Murakami

- Hân Hương

- Heiko Buschke

- Heinrich Heine

- Henri Michaux

- Henry David Thoreau

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

- Heriberto Araújo

- Hermann Hesse

- Hiền Trang

- Hiệp Ikaria

- Hiệu Minh

- Hiếu Tân

- Ho Lai-Ming

- Hòa Bình Lê

- Hoa Níp

- Hoài Hương

- Hoài Nam

- Hoài Phương

- Hoài Thanh

- Hoài Việt

- Hoài Ziang Duy

- Hoan Doan

- Hoàn Nguyễn

- Hoàng Ánh

- Hoàng Anh Tuấn

- Hoàng Cát

- Hoàng Cầm

- Hoàng Chí Hiếu

- Hoàng Chính

- Hoàng Cường Long

- Hoàng Dũng

- Hoàng Dương Tuấn

- Hoàng Đăng Khoa

- Hoàng Đỗ

- Hoàng Đông

- Hoàng Đức Truật

- Hoàng Hà

- Hoàng Hải Thủy

- Hoàng Hải Vân

- Hoảng Hãn

- Hoàng Hôn

- Hoàng Hưng

- Hoàng Khởi Phong

- Hoàng Kim Oanh

- Hoàng Lại Giang

- Hoàng Lan

- Hoàng Lan Anh

- Hoàng Lan Chi

- Hoàng Lê

- Hoàng Lệ

- Hoàng Linh

- Hoàng Long

- Hoàng Mai Ðạt

- Hoàng Mạnh Hải

- Hoàng Minh Trí

- Hoàng Minh Tường

- Hoàng Nam

- Hoàng Nga

- Hoàng Ngọc Biên

- Hoàng Ngọc Hiến

- Hoàng Ngọc Nguyên

- Hoàng Ngọc Tuấn

- Hoàng Nguyễn

- Hoàng Nguyên Vũ

- Hoàng Nhơn

- Hoàng Nhuận Cầm

- Hoàng Phong Tuấn

- Hoàng Phủ Ngọc Tường

- Hoàng Quân

- Hoàng Quốc Dũng

- Hoàng Quốc Hải

- Hoàng Thị Hường

- Hoàng Thị Thu Thủy

- Hoàng Thu Phố

- Hoàng Thúy

- Hoàng Thuỵ Anh

- Hoàng Tiến

- Hoàng Trung Thông

- Hoàng Tuấn Công

- Hoàng Tuấn Phổ

- Hoàng Tùng

- Hoàng Tuỵ

- Hoàng Tư Giang

- Hoàng Văn Sơn

- Hoàng Việt

- Hoàng Vũ Sơn

- Hoàng Vũ Thuật

- Hoàng Xuân Phú

- Hoàng Xuân Sơn

- Hoàng Xuân Tuyền

- Hoàng Yến

- Horst Bienek

- Howard Gardner

- Hồ Anh Thái

- Hồ Bạch Thảo

- Hồ Bất Khuất

- Hồ Diệu Vân

- Hồ Dzếnh

- Hồ Đắc Vũ

- Hồ Đình Nghiêm

- Hồ Hải Thụy

- Hồ Hữu Tường

- Hồ Minh Tâm

- Hồ Ngọc Đại

- Hồ Như

- Hồ Phú Bông

- Hồ Tịnh Tình

- Hồ Trường An

- Hồ Tú Bảo

- Hội những người ủng hộ GS. Chu Hảo

- Hồng Anh

- Hồng Hoang

- Hồng Lê Thọ

- Hồng Phú

- Huệ Hương Hoàng

- Huguette Bertrand

- Huong Nguyen

- Huy Bảo

- Huy Cận

- Huy Đức

- Huy Tưởng

- Huyền Thương

- Huỳnh Duy Lộc

- Huỳnh Hoa

- Huỳnh Hữu Uỷ

- Huỳnh Hữu Ủy

- Huỳnh Kim Báu

- Huỳnh Kim Quang

- Huỳnh Lê Nhật Tấn

- Huỳnh Liễu Ngạn

- Huỳnh Ngọc Chênh

- Huỳnh Như Phương

- Huỳnh Sơn Phước

- Huỳnh Tấn Mẫm

- Huỳnh Thế Du

- Huỳnh Thục Vy

- Huỳnh Trọng Khang

- Huỳnh Tuấn Anh

- Hứa Chương Nhuận

- Hứa Lập Chí

- Hương Lan

- Hường Thanh

- Hương Thủy

- Hữu Danh

- Hữu Đông

- Hữu Loan

- Hữu Mai

- Hữu Phương

- Ian Bui

- Ian Johnson

- Igor Poglazov

- Iio Sōgi

- Ilza Burchett

- Inrasara

- Iris Radisch

- Isabella Kwai

- Issa

- Issac Bashevis Singer

- Italo Calvino

- Iya Kiva

- J. M. Lotman

- J.B Nguyễn Hữu Vinh

- Jacques Attali

- Jacques Prévert

- Jake Johnson

- James Borton

- James Daniel Spears

- James G. Zumwalt

- James Grossman

- James Joyce

- James Poniewozik

- James Stavridis

- James WrightJuan Felipe Herrera

- Jang Kều

- Janos Kornai

- Jared Carters

- Jason Lopata

- Jason Morris-Jung

- Jay Nordlinger

- Jaya K.

- Jean Chesnaux

- Jean d'Ormesson

- Jean Piaget

- Jean Przyluski

- Jean Toomer

- Jean-Jacques Brochier

- Jean-Jacques Roth

- Jean-Louis Rocca

- Jean-Luc Chalumeau

- Jean-Marc Roberts

- Jean-Patrick Géraud

- Jean-Paul Sartre

- Jefferson Cowie

- Jeffrey Hanfover

- Jeffrey Nall

- Jessica Swoboda

- Jessie Yeung

- Jiayang Fan

- Jimmy Carter

- Joan Hua

- João Guimarães Rosa

- Joaquin Nguyễn Hòa

- John Barrow

- John Cheever

- John D. Howard

- John Freeman

- John Keane

- John McCain

- Jon Fosse

- Jonathan Dee

- Jonathan London

- Jonathan Scott Holloway

- Jörg Wischermann

- Jorge Amado

- Jorge Luis Borges

- Joschka Fischer

- Josée Lapointe

- Joseph Wong

- Joseph Wright

- Josh Rogin

- Joshua Rothman

- Juan Pablo Cardenal

- Juan Pablo Cardenal & Heriberto Araújo

- Julia Cagé

- Julio Cortázar

- Jun’ichiro Tanizaki

- Kahil Gibral

- Kai Hoàng

- Kale

- Kalynh Ngô

- Kamel Daoud

- Kao Phú

- Kap Seol

- Karel Appel

- Karen Tongson

- Kate Chopin

- Kazuo Shiraga

- Kenneth Nguyen

- Kenzaburo Oe

- Keorapetse Kgositsile

- Kerstin Holm

- Kều Jang

- Kha Lương Ngãi

- Kha Tiệm Ly

- Khải Đơn

- Khái Hưng

- Khaled Juma

- Khaly Chàm

- Khang Quốc Ngọc

- Khánh

- Khánh Bình

- Khánh Duy

- Khánh Ly

- Khánh Mai

- Khanh Nguyen

- Khanh Pham

- Khánh Phương

- Khánh Trâm

- Khánh Trường

- Khét

- Khế Iêm

- Khiêm Nhu

- Khổng Đức Thiêm

- Khuất Đẩu

- Khuất Thu Hồng

- Khuê Minh Nguyệt

- Khuê Phạm

- Khuyết Thư

- Kiệm Hoàng

- Kiến Văn

- Kiệt Anh Hùng

- Kiệt Tấn

- Kiều Duy Vĩnh

- Kiều Loan

- Kiều Mai Sơn

- Kiều Maily

- Kiều Phong

- Kiều Thị An Giang

- Kim Ân

- Kim Chi

- Kim Dung

- Kim Hạnh

- Kim Thúy

- Kim Trần

- Kim Yi-deum

- Kinh Bắc

- Kính Hòa

- Klaus Wiegerefe

- Kobayashi Issa

- Kúm

- Kumar Vikram

- Kurt-Martin Mayer

- Kỳ Duyên

- Kyoko Numano

- L. N. Tolstoy

- L. V. H.

- La Khắc Hoà

- La Khắc Hòa

- Lã Nguyên

- Lại Nguyên Ân

- Lam Điền

- Lam Hạnh

- Lam Ngọc

- Lam Thái Hòa

- Lan Nguyên

- Lang Anh

- Langston Hughes

- LAP

- Larry Diamond

- Lars Vargö

- László Krasznahorkai

- Laura Cappelle

- Laurent Sagalovitsch

- Lawrence Ferlinghetti

- Lâm Chương

- Lâm Duyên

- Lâm Hạnh

- Lâm Lê

- Lâm Ngân Mai

- Lâm Quang Mỹ

- Lâm Thị Mỹ Dạ

- Lenin

- Leon Trotsky

- Leonard Cohen

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Lê An Thế

- Lê Anh Hoài

- Lê Anh Hùng

- Lê Ân

- Lê Bá Đảng

- Lê Bích Vượng

- Lê Chiều Giang

- Lê Công Định

- Lê Công Giàu

- Lê Công Tư

- Lê Ðình Nhất Lang

- Lê Dũng

- Lê Duy Nam

- Lê Đạt

- Lê Đăng Doanh

- Lê Đình Cai

- Lê Đình Khẩn

- Lê Đình Thắng

- Lê Đỗ Huy

- Lê Đức Dục

- Lê Đức Thôn

- Lê Giang Trần

- Lê Hải

- Lệ Hằng

- Lê Hiệp

- Lê Hoài Nguyên

- Lê Hoàng Diễm Trang

- Lê Hoàng Lân

- Lê Học Lãnh Vân

- Lê Hồ Quang

- Lê Hồng Hà

- Lê Hồng Hiệp

- Lê Hồng Lâm

- Lê Hùng

- Lê Hùng Vọng

- Lê Huyền Ái Mỹ

- Lê Huỳnh Lâm

- Lê Hữu

- Lê Hữu Khoá

- Lê Hữu Khóa

- Lê Hữu Nam

- Lê Kế Lâm

- Lê Khải

- Lê Kim Duy

- Lê Ký Thương

- Lê Lạc Giao

- Lê Luân

- Lê Mã Lương

- Lê Mai

- Lê Mai Lĩnh

- Lê Mạnh Chiến

- Lê Mạnh Đức

- Lê Minh

- Lê Minh Chánh

- Lê Minh Hà

- Lê Minh Hiền

- Lê Minh Khuê

- Lê Minh Phong

- Lê Ngân Hằng

- Lê Ngọc Luân

- Lê Ngọc Sơn

- Lê Nguyễn

- Lê Nguyễn Duy Hậu

- Lê Nguyễn Hương Trà

- Lê Nguyên Long

- Lê Nguyên Vỹ

- Lê Như Bình

- Lê Oa Đằng

- Lê Phan

- Lê Phú Khải

- Lê Quang

- Lê Quang Đức

- Lê Quảng Hà

- Lê Quang Hợp

- Lê Quang Thành

- Lê Quân

- Lê Quốc Anh

- Lê Quỳnh

- Lê Quỳnh Mai

- Lê Sa Long

- Lê Si Na

- Lê Sơn

- Lê Tất Đạt

- Lê Tất Điều

- Lê Thanh Dũng

- Lê Thanh Hải

- Lê Thanh Phong

- Lê Thanh Trường

- Lê Thân

- Lê Thế Thắng

- lê thi diem thuý

- Lê Thị Hồng Minh

- Lê Thị Huệ

- Lê Thị Hường

- Lê Thị Oanh

- Lê Thị Thanh Tâm

- Lê Thị Thấm Vân

- Lê Thiết Cương

- Lê Thiếu Nhơn

- Lê Thọ Bình

- Lê Thời Tân

- Lê Thời Thôi

- Lê Thu Hiền

- Lê Thúy Bảo Liên

- Lê Tiên Long

- Lê Trí Tuệ

- Lê Trinh

- Lê Trọng Nghĩa

- Lê Trọng Nguyễn

- Lê Trung Tĩnh

- Lê Trường Thanh

- Lê Tuấn Huy

- Lê Tuyết Hạnh

- Lê Văn Bỉnh

- Lê Văn Hảo

- Lê Văn Hiếu

- Lê Văn Hòa

- Lê Văn Hùng Vĩ

- Lê Văn Luân

- Lê Văn Sơn

- Lê Văn Trung

- Lê Văn Tùng

- Lê Vĩnh Tài

- Lê Vĩnh Triển

- Lê Vũ Trường Giang

- Lê Xuân Khoa

- Lê Xuyên

- Li Edelkoort

- Li Tana

- Li Zhongqin

- Liêu Diệc Vũ

- Liêu Thái

- Liễu Trương

- Linh Nguyên

- Linh Văn

- Linh Vân

- Linh-Chân Brown

- LKH

- Lorca

- Louis Aragon

- Louise Glück

- Lộc Vàng

- Lợi Phan Mai

- Luân Hoán

- Ludwig von Mises

- Luke Hunt

- Luke Turner

- Lữ Kiều

- Lữ Quỳnh

- Lương Đào

- Lương Thiệu Quân

- Lương Thư Trung

- Lưu Á Châu

- Lưu Bình Nhưỡng

- Lưu Diệu Vân

- Lưu Đình Long

- Lưu Đức Trung

- Lưu Hà

- Lưu Hiểu Ba

- Lưu Khánh Thơ

- Lưu Mê Lan

- Lưu Minh Hải

- Lưu Na

- Lưu Nhi Dũ

- Lưu Quang Vũ

- Lưu Thuỷ Hương

- Lưu Thủy Hương

- Lưu Trọng Tưởng

- Lưu Trọng Văn

- Lưu Uyên Khôi

- Lý Đợi

- Lý Gia Trung

- Ly Hoàng Ly

- Lý Ngang

- Ly Phạm

- Lý Quang Hoàn

- Lý Thanh

- Lý Tiến Dũng

- Lý Toàn Thắng

- Lý Trực Dũng

- Lý Xuân Hải

- Lydia Davis

- Lynh Bacardi

- LysP

- M. Gorky

- M. Trần

- M.L. Gasparov

- Mạc Phong Tuyền

- Mạc Văn Trang

- Mạc Việt Hồng

- Mạch Nha

- Mạch Quang Thắng

- Madeleine Riffaud

- Madlovics Bálint

- Magyar Bálint

- Mahmoud Darwish

- Mai An Nguyễn Anh Tuấn

- Mai Anh Tuấn

- Mai Bá Ấn

- Mai Bá Kiếm

- Mai Chanh

- Mai Đỗ

- Mai Hiền

- Mai Khôi

- Mai Kim Ngọc

- Mai Lý

- Mai Nhật

- Mai Ninh

- Mai Quốc Ấn

- Mai Quỳnh

- Mai Quỳnh Nam

- Mai Sơn

- Mai Thái Lĩnh

- Mai Thanh Sơn

- Mai Thảo

- Mai Tú Ân

- Mai Văn Hoan

- Mai Văn Phấn

- Mai Văn Tính

- Maki Starfield

- Mamleev

- Mạnh Kim

- Manuel Casimiro

- Mão Xuyên

- Marc Andrus

- Marcel Reich-Ranicki

- Marci Shore

- Marco Ferrarese

- Margarita Lyutova

- Marguerite Duras

- Maria Donovan

- Maria Ressa

- Marie Lê Thị Hoa

- Mario Vargas Llosa

- Marion Hennebert

- Mark B. Hamilton

- Mark Binelli

- Mark Frankland

- Mark Osaki

- Mark Strand

- Marta Hillers

- Martin Jankowski

- Martin Kulldorff

- Marty Robbins

- Mary Morose

- Mary Walsh

- Matei Vişniec

- Mathias Mayer

- Matthew Clayfield

- Matthew Crawford

- Maurice Blanchot

- Maximilian Steinbeis

- May

- Maya Angelou

- Mặc Đỗ

- Mặc Lâm

- Mân Côi

- McAmmond Nguyễn Thị Tư

- Media Văn Việt

- Mia Pluger

- Michael Burawoy

- Michael Scammell

- Miêng

- Mike Ives

- Mikhail Shishkin

- Mikhail Sholokhov

- Mikhail Viktorovich Zygar

- Milan Kundera

- Mimmi Diệu Hường Bergström

- MInh Anh

- Minh Huệ

- Minh Hùng

- Minh Luật

- Minh Quang – Lê Chiên

- Minh Quang Ho

- Minh Tâm

- Minh Thùy

- Minh Thư

- Minh Toàn

- Minh Tuấn

- Minh Tự

- Mireille Sacotte

- Miura Chora

- Monica Berlin

- Mường Mán

- Mỹ Hằng

- Mỹ Lan

- N. S. Khrushchev

- Nadine Murtaja

- Nam Dao

- Nam Dao Nguyễn Mạnh Hùng

- Nam Đan

- Nam Đông

- Nam Nguyên

- Nam Sơn

- Naowarat Pongpaiboon

- Natalia lacovelli

- Nataliya Zhynkina

- Natsume Sōseki

- Nay Aung

- ng. anhanh

- Ng.Uyển Nicole Dương

- Ngải Vị VỊ

- Ngân Xuyên

- Nghệ thuật

- Nghĩa Đặng

- Nghiêm Lương Thành

- Nghiêm Phương Mai

- Nghiêm Thanh Hương

- Nghiêm Xuân Hồng

- Nghiên Cứu Phê Bình

- Ngo Thu

- Ngọc Anh

- Ngọc Duy Phan

- Ngoc Hien Bui

- Ngọc Linh

- Ngô Anh Tuấn

- Ngô Bảo Châu

- Ngô Đình Thẩm

- Ngô Đồng

- Ngô Hương Giang

- Ngô Khắc Tài

- Ngộ Không Phí Ngọc Hùng

- Ngô Kim Khôi

- Ngô Kim-Khôi

- Ngô Liêm Khoan

- Ngô Lực

- Ngô Mai Phong

- Ngô Mạnh Hùng

- Ngô Minh

- Ngô Minh Khôi

- Ngô Ngọc Loan

- Ngô Ngọc Trai

- Ngô Nguyên Dũng

- Ngô Nhật Đăng

- Ngô Quốc Phương

- Ngô Quốc Thịnh

- Ngô Thế Vinh

- Ngô Thị Kim Cúc

- Ngô Thị Thanh Lịch

- Ngô Thị Thu Ngần

- Ngô Tùng Phong

- Ngô Tự Lập

- Ngô Văn

- Ngô Văn Giá

- Ngô Viết Nam Sơn

- Ngô Viết Trọng

- Ngô Việt Trung

- Ngô Vĩnh Long

- Ngô Xuân Hội

- Ngô Xuân Phúc

- Ngô Xuân Thảo

- Ngu Yên

- Nguyen Duc Thanh

- Nguyễn Hải Hoành

- Nguyễn Anh Dũng

- Nguyễn Anh Tuấn

- Nguyễn Anh Tuấn - đạo diễn

- Nguyễn Bá Chung

- Nguyễn Bách Việt

- Nguyễn Bảo Chân

- Nguyễn Bắc Sơn

- Nguyên Bình

- Nguyễn Bính

- Nguyễn Cảnh Bình

- Nguyên Cầm

- Nguyên Cẩn

- Nguyên Chánh

- Nguyễn Chí Hoan

- Nguyễn Chí Thuật

- Nguyễn Chí Trung

- Nguyễn Chí Tuyến

- Nguyễn Chinh Trung

- Nguyễn Cung Thông

- Nguyễn Cường

- Nguyễn Danh Bằng

- Nguyễn Danh Huế

- Nguyễn Danh Lam

- Nguyễn Ðăng Thường

- Nguyễn Duy

- Nguyễn Dương Quang

- Nguyễn Đạt

- Nguyễn Đắc Kiên

- Nguyễn Đắc Xuân

- Nguyễn Đăng Điệp

- Nguyễn Đăng Hưng

- Nguyễn Đăng Khoa

- Nguyễn Đăng Mạnh

- Nguyễn Đăng Na

- Nguyễn Đăng Quang

- Nguyễn Đăng Thường

- Nguyễn Đình Ấm

- Nguyễn Đình Bin

- Nguyễn Đình Bổn

- Nguyễn Đình Chú

- Nguyễn Đình Cống

- Nguyễn Đình Đăng

- Nguyễn Đình Huỳnh

- Nguyễn Đình Phượng Uyển

- Nguyễn Đình Thắng

- Nguyễn Đình Thi

- Nguyễn Đình Toàn

- Nguyễn Đông A

- Nguyễn Đổng Chi

- Nguyễn Đông Thức

- Nguyễn Đức

- Nguyễn Đức Dương

- Nguyễn Đức Hiệp

- Nguyễn Đức Mậu

- Nguyễn Đức Sơn

- Nguyễn Đức Thắng

- Nguyễn Đức Tiến

- Nguyễn Đức Tùng

- Nguyễn Đức Tường

- Nguyễn Gia Trí

- Nguyên Giác

- Nguyên Giác Phan Tấn Hải

- Nguyễn Hà Luân

- Nguyễn Hải Hoành

- Nguyễn Hải Yến

- Nguyễn Hàn Chung

- Nguyễn Hiến Lê

- Nguyễn Hoa Lư

- Nguyễn Hoài Nam

- Nguyễn Hoài Văn

- Nguyễn Hoài Vân

- Nguyễn Hoàn

- Nguyễn Hoàn Nguyên

- Nguyễn Hoàng Ánh

- Nguyễn Hoàng Anh Thư

- Nguyễn Hoàng Diệu Thủy

- Nguyễn Hoàng Diệu Thúy

- Nguyễn Hoàng Giao

- Nguyễn Hoàng Linh

- Nguyễn Hoàng Trung

- Nguyễn Hoàng Văn

- Nguyễn Hồng Anh

- Nguyễn Hồng Giao

- Nguyễn Hồng Hưng

- Nguyễn Hồng Lam

- Nguyễn Hồng Nhung

- Nguyễn Hồng Thục

- Nguyễn Huệ Chi

- Nguyễn Hùng

- Nguyễn Huy Hoàng

- Nguyễn Huy Thiệp

- Nguyễn Huy Vũ

- Nguyên Hưng

- Nguyễn Hưng Quốc

- Nguyễn Hương

- Nguyễn Hữu Đễ

- Nguyễn Hữu Hồng Minh

- Nguyễn Hữu Liêm

- Nguyễn Hữu Nhật

- Nguyễn Hữu Sơn

- Nguyễn Hữu Thiết

- Nguyễn Hữu Việt Hưng

- Nguyễn Hữu Vinh

- Nguyễn kc Hậu

- Nguyễn Khải

- Nguyễn Khánh Duy

- Nguyễn Khánh Trường

- Nguyễn Khắc An

- Nguyễn Khắc Bình

- Nguyễn Khắc Mai

- Nguyễn Khắc Ngân Vi

- Nguyễn Khắc Phê

- Nguyễn Khắc Phi

- Nguyễn Khắc Phục

- Nguyễn Khiêm

- Nguyễn Khôi

- Nguyễn Kiến Phước

- Nguyễn Kiều Dung

- Nguyễn Kiều Hưng

- Nguyễn Kim Hưng

- Nguyên Lạc

- Nguyễn Lam Điền

- Nguyễn Lãm Thắng

- Nguyễn Lan Phương

- Nguyễn Lâm Cẩn

- Nguyễn Lân Bình

- Nguyễn Lân Thắng

- Nguyễn Lê Hồng Hưng

- Nguyễn Lê Tuyên

- Nguyễn Lệ Uyên

- Nguyễn Linh Giang

- Nguyễn Linh Quang

- Nguyễn Lộ Trạch

- Nguyễn Luận

- Nguyễn Lương Hải Khôi

- Nguyễn Lương Ngọc

- Nguyễn Lương Thịnh

- Nguyễn Lương Vỵ

- Nguyễn Mai

- Nguyễn Man Nhiên

- Nguyễn Mạnh An Dân

- Nguyễn Mạnh Côn

- Nguyễn Mạnh Đẩu

- Nguyễn Mạnh Tiến

- Nguyễn Manh Trinh

- Nguyễn Mạnh Trinh

- Nguyễn Mạnh Tuấn

- Nguyễn Mạnh Tường

- Nguyễn Minh Anh

- Nguyễn Minh Hòa

- Nguyễn Minh Kính

- Nguyễn Minh Nhị

- Nguyễn Minh Nhựt

- Nguyễn Minh Thuyết

- Nguyễn Mộng Giác

- Nguyên Ngọc

- Nguyễn Ngọc Chu

- Nguyễn Ngọc Đức

- Nguyễn Ngọc Giao

- Nguyễn Ngọc Hoa

- Nguyễn Ngọc Lanh

- Nguyễn Ngọc Liễm

- Nguyễn Ngọc Lung

- Nguyễn Ngọc Phương

- Nguyễn Ngọc Tâm

- Nguyễn Ngọc Thiện

- Nguyễn Ngọc Tú Anh

- Nguyễn Ngọc Tư

- Nguyên Nguyên

- Nguyễn Nguyên

- Nguyễn Nguyên Bình

- Nguyễn Nguyệt Cầm

- Nguyễn Nhật Lệ

- Nguyễn Nhật Tín

- Nguyên Nhi

- Nguyễn Như Huy

- Nguyễn Như Mây

- Nguyễn Phạm Hùng

- Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai

- Nguyễn Phú Yên

- Nguyễn Phúc Vĩnh Ba

- Nguyễn Phượng

- Nguyễn Phương Đình

- Nguyễn Phương Mai

- Nguyễn Phương Mạnh

- Nguyễn Quang

- Nguyễn Quang A

- Nguyễn Quang Bình

- Nguyễn Quang Duy

- Nguyễn Quang Dy

- Nguyễn Quang Đồng

- Nguyễn Quang Hồng

- Nguyễn Quang Hưng

- Nguyễn Quang Lập

- Nguyễn Quang Thạch

- Nguyễn Quang Thân

- Nguyễn Quang Thiều

- Nguyễn Quang VInh

- Nguyễn Quân

- Nguyễn Quốc Bảo

- Nguyễn Quốc Chánh

- Nguyễn Quốc Chính

- Nguyễn Quốc Lâm

- Nguyễn Quốc Tấn Trung

- Nguyễn Quốc Thái

- Nguyễn Quốc Toàn

- Nguyễn Quốc Trụ

- Nguyễn Quốc Tuấn

- Nguyễn Quốc Vương

- Nguyễn Quỳnh Hương

- Nguyên Sa

- Nguyễn Sĩ Dũng

- Nguyễn Sơn Lâm

- Nguyễn Sỹ Phương

- Nguyễn Sỹ Tế

- Nguyễn Tà Cúc

- Nguyễn Tài Cẩn

- Nguyễn Tấn Cứ

- Nguyễn Tất Nhiên

- Nguyễn Thạch Giang

- Nguyễn Thái Hòa

- Nguyễn Thái Hợp

- Nguyễn Thái Sơn

- Nguyễn Thái Tuấn

- Nguyễn Thanh Bình

- Nguyễn Thanh Châu

- Nguyễn Thanh Giang

- Nguyễn Thanh Hiện

- Nguyễn Thanh Hùng

- Nguyễn Thanh Huy

- Nguyễn Thanh Huyền

- Nguyễn Thanh Mỹ

- Nguyễn Thành Nam

- Nguyễn Thanh Nghị

- Nguyễn Thanh Nguyệt

- Nguyễn Thành Phong

- Nguyễn Thanh Sơn

- Nguyễn Thành Sơn

- Nguyễn Thanh Tâm

- Nguyễn Thành Thi

- Nguyễn Thanh Tuyền

- Nguyễn Thanh Văn

- Nguyễn Thanh Việt

- Nguyễn Thế Hùng

- Nguyễn Thế Thanh

- Nguyễn Thị Ái Tiên

- Nguyễn Thị Bích Hậu

- Nguyễn Thị Bích Ngà

- Nguyễn Thị Bình

- Nguyễn thị Cỏ May

- Nguyễn Thị Dư Khánh

- Nguyễn Thị Hải

- Nguyễn Thị Hậu

- Nguyễn Thị Hiền

- Nguyễn Thị Hoàng

- Nguyễn Thị Hoàng Bắc

- Nguyễn Thị Hồng

- Nguyễn Thị Khánh Minh

- Nguyễn Thị Khánh Trâm

- Nguyễn Thị Kim Chi

- Nguyễn Thị Kim Phụng

- Nguyễn Thị Kim Thoa

- Nguyễn Thị Minh Ngọc

- Nguyễn Thị Minh Thái

- Nguyễn Thị Minh Thương

- Nguyễn Thị Ngọc Hải

- Nguyễn Thị Ngọc Nhung

- Nguyễn Thị Oanh

- Nguyễn Thị Phước

- Nguyễn Thị Thanh Bình

- Nguyễn Thị Thanh Hải

- Nguyễn Thị Thanh Lưu

- Nguyễn Thị Thanh Xuân

- Nguyễn Thị Thanh Yến

- Nguyễn Thị Thảo An

- Nguyễn Thị Thúy Hạnh

- Nguyễn Thị Thùy Linh

- Nguyễn Thị Thụy Vũ

- Nguyễn Thị Thuyền

- Nguyễn Thị Tịnh Thy

- Nguyễn Thị Từ Huy

- Nguyễn Thị Vinh

- Nguyễn Thiện Tống

- Nguyễn Thiện Tơ

- Nguyễn Thói Đời

- Nguyễn Thông

- Nguyễn Thu Quỳnh

- Nguyễn Thu Trang

- Nguyễn Thụy Anh

- Nguyễn Thùy Dương

- Nguyễn Thúy Hạnh

- Nguyễn Thụy Long

- Nguyễn Thuỵ Phương

- Nguyễn Thùy Song Thanh

- Nguyễn Thỵ

- Nguyễn Thy Anh

- Nguyễn Tiến Dũng

- Nguyễn Tiến Lập

- Nguyễn Tiến Trung

- Nguyễn Tiến Văn

- Nguyễn Trần Bạt

- Nguyễn Tri Phương Đông

- Nguyễn Triệu Nam

- Nguyễn Trọng Bình

- Nguyễn Trọng Chức

- Nguyễn Trọng Huân

- Nguyễn Trọng Khôi

- Nguyễn Trọng Tạo

- Nguyễn Trung

- Nguyễn Trung Bảo

- Nguyễn Trung Dân

- Nguyễn Trung Hiếu

- Nguyễn Trung Kiên

- Nguyễn Trung Thuần

- Nguyễn Trường Giang

- Nguyễn Trường Huy

- Nguyễn Trường Uy

- Nguyễn Tuấn

- Nguyễn Tuấn Anh

- Nguyễn Tuấn Khoa

- Nguyễn Tùng

- Nguyễn Tùng Linh

- Nguyễn Tuyết Lan

- Nguyễn Tuyết Lộc

- Nguyễn Tư Nghiêm

- Nguyễn Tử Siêm

- Nguyễn Tường Bách

- Nguyễn Tường Thiết

- Nguyễn Tường Thụy

- Nguyễn Ước

- Nguyễn Vạn An

- Nguyễn Vạn Phú

- Nguyễn Văn

- Nguyễn Văn Ba

- Nguyễn Văn Chính

- Nguyễn Văn Ðậu

- Nguyễn Văn Dũng

- Nguyễn Văn Đài

- Nguyễn Văn Gia

- Nguyễn Văn Hạnh

- Nguyễn Văn Hiệp

- Nguyễn Văn Hòa

- Nguyễn Văn Hùng

- Nguyễn Văn Huyên

- Nguyễn Văn Lợi

- Nguyễn Văn Lục

- Nguyễn Văn Miếng

- Nguyễn Văn Nghệ

- Nguyễn Văn Nho

- Nguyễn Văn Phong

- Nguyễn Văn Phú

- Nguyễn Văn Phước

- Nguyễn Văn Sâm

- Nguyễn Văn Sơn

- Nguyễn Văn Tao

- Nguyễn Văn Thiệu

- Nguyễn Văn Thọ

- Nguyễn Văn Trọng

- Nguyễn Văn Trung

- Nguyễn Văn Tuấn

- Nguyễn Văn Vĩnh

- Nguyễn Văn Xuân

- Nguyễn Vi Khải

- Nguyễn Vi Yên

- Nguyễn Viện

- Nguyên Việt

- Nguyễn Việt Anh

- Nguyễn Việt Chiến

- Nguyễn Viết Dũng

- Nguyễn Viết Lãm

- Nguyễn Vĩnh Nguyên

- Nguyễn Vũ Hiệp

- Nguyễn Vũ Tiềm

- Nguyễn Vỹ

- Nguyễn Vy Khanh

- Nguyễn Xuân Diện

- Nguyễn Xuân Hằng

- Nguyễn Xuân Hoàng

- Nguyễn Xuân Hưng

- Nguyễn Xuân Khánh

- Nguyễn Xuân Khoát

- Nguyễn Xuân Nghĩa

- Nguyễn Xuân Nha

- Nguyễn Xuân Quang

- Nguyễn Xuân Thiệp

- Nguyễn Xuân Thọ

- Nguyễn Xuân Tiệp

- Nguyễn Xuân Tường Vy

- Nguyễn Xuân Vượng

- Nguyễn Xuân Xanh

- Nguyễn Ý Thuần

- Nguyên Yên

- Nguyễn-Chương Mt

- Nguyễn-hòa-Trước

- Nguyệt Chu

- Nguyệt Quỳnh

- Nguyệt Vi

- Ngự Thuyết

- Người Buôn Gió

- Ngyễn Trung Bảo

- Nh. Tay Ngàn

- Nhã

- Nhã Ca

- Nhã Duy

- Nhã Thuyên

- Nhan Do Thanh

- Nhân Hồng

- Nhật Chiêu

- Nhật Lệ

- Nhất Linh

- Nhật Thanh

- Nhật Tiến

- Nhật Tuấn

- Nhất Uyên

- Nhị Linh

- Nhị Ngã

- Nhóm Vì một Hà Nội xanh

- Như Huy

- Như Không

- Như Quỳnh

- Như Quỳnh de Prelle

- Như Ý

- Nhược Thủy

- Niall Ferguson

- Nick Hilden

- Nicolas Casey

- Nikulin

- Nina McPherson

- Ninh Dương

- Ninh Kiều

- Nobert Hummelt

- Nông Hồng Diệu

- NP Phan

- Obama

- Ocean Vương

- Octavio Paz

- Ogden Nash

- Oksana Zabuzhko

- Oleg Kashin

- Ondrej Slowik

- onggiaolang

- Orlando Figes

- Orwell

- Oscar Salemink

- Oscar Wilde

- Pablo Neruda

- Pablo Picasso

- Palmer

- Pamela N. Corey

- Patrick Frater

- Patrick Lodge

- Paul Auster

- Paul Celan

- Paul Éluard

- Paul Hoover

- Paul Mendez

- Paul Mozur

- Paul Theroux

- Paul-François Paoli

- Paulus Lê Sơn

- Pavel Basinsky

- Pavel Basynski

- Pavlo Vyshebaba

- Paweł Kubiak

- Pawel Kuczynski

- Paweł Łepkowski

- Percy Mabandu

- Pervez Hoodbhoy

- Peter B. Zinoman

- Peter Bradshaw

- Peter Hansen

- Peter Harvey

- Peter Kleiner

- Peter Singer

- Phạm Anh Tuấn

- Phạm Biểu Tâm

- Phạm Cảnh Thượng

- Phạm Cao Hoàng

- Phạm Châu

- Phạm Chí Dũng

- Phạm Chi Lan

- Phạm Chu Sa

- Phạm Công Luận

- Phạm Công Thiện

- Phạm Công Trứ

- Phạm Công Út

- Phạm Duy

- Phạm Duy Nghĩa

- Phạm Đình Chương

- Phạm Đình Trọng

- Phạm Đình Vy

- Phạm Đoan Trang

- Phạm Hải Anh

- Phạm Hải Âu

- Phạm Hiền Mây

- Phạm Hoàng Quân

- Phạm Hồng Sơn

- Phạm Hùng Việt

- Phạm Huy Thông

- Phạm Khánh Duy

- Phạm Khiêm Ích

- Phạm Kiều Tùng

- Phạm Kỳ Đăng

- Phạm Lệ Quyên

- Phạm Lê Vương Các

- Phạm Linh

- Phạm Lưu Vũ

- Phạm Minh Hoàng

- Phạm Minh Ngọc

- Phạm Minh Quân

- Phạm Minh Trung

- Phạm Ngọc Lư

- Phạm Ngọc Thái

- Phạm Ngọc Tiến

- Phạm Nguyên Trường

- Phạm Ngữ

- Phạm Phan Long

- Phạm Phú Cường

- Phạm Phú Hải

- Phạm Phú Minh

- Phạm Phú Phong

- Phạm Phú Thứ

- Phạm Phú Viết

- Phạm Phúc Thịnh

- Phạm Phương

- Phạm Quang Ái

- Phạm Quang Long

- Phạm Quang Trung

- Phạm Quang Tuấn

- Phạm Sỹ Sáu

- Phạm Tăng

- Phạm Thành

- Phạm Thành Hưng

- Phạm Thanh Nghiên

- Phạm Thảo Nguyên

- Phạm Thế Cường

- Phạm Thị

- Phạm Thị Anh Nga

- Phạm Thị Điệp Giang

- Phạm Thị Hoài

- Phạm Thị Kiều Ly

- Phạm Thị Ngọc

- Phạm Thị Phương

- Phạm Thiên Ân

- Phạm Thiên Thư

- Phạm Tín An Ninh

- Phạm Toàn

- Phạm Trần

- Phạm Trọng Chánh

- Phạm Trung Nghĩa

- Phạm Tuấn

- Phạm Tư Thanh Thiện

- Phạm Tường Vân

- Phạm Văn

- Phạm Văn Khoái

- Phạm Văn Quang

- Phạm Văn Tình

- Phạm Văn Vũ

- Pham Viem Phuong

- Phạm Viêm Phương

- Phạm Viết Đào

- Phạm Việt Hưng

- Phạm Vũ Lửa Hạ

- Phạm Xuân Đài

- Phạm Xuân Hùng

- Phạm Xuân Nguyên

- Phạm Xuân Trường

- Phan An Sa

- Phan Ba

- Phan Bội Châu

- Phan Cẩm Thượng

- Phan Châu Thành

- Phan Cự Đệ

- Phan Dương Hiệu

- Phan Đan

- Phan Đạo

- Phan Đắc Lữ

- Phan Đình Diệu

- Phan Độc Lập

- Phan Hải-Đăng

- Phan Hồng Giang

- Phan Huy Chú

- Phan Huy Dũng

- Phan Huy Đường

- Phan Huy Lê

- Phan Huyền Thư

- Phan Kế Toại

- Phan Khôi

- Phan Kim Hổ

- Phan Lặng Yên

- Phan Mạnh Quỳnh

- Phan Nam Sinh

- Phan Ngọc

- Phan Nguyên

- Phan Nhật Nam

- Phan Nhiên Hạo

- Phan Ni Tấn

- Phan Phương Đạt

- Phan Quang

- Phan Quỳnh Trâm

- Phan Tấn Hải

- Phan Tấn Uẩn

- Phan Thanh Bình

- Phan Thanh Sơn Nam

- Phan Thanh Tâm

- Phan Thắng

- Phan Thế Hải

- Phan Thị Hà Dương

- Phan Thị Kim Phúc

- Phan Thị Trọng Tuyển

- Phan Thị Vàng Anh

- Phan Thu Vân

- Phan Thuý Hà

- Phan Thúy Hà

- Phan Trang Hy

- Phan Trí Đỉnh

- Phan Trọng Hoàng Linh

- Phan Trọng Văn

- Phan Văn Giưỡng

- Phan Văn Song

- Phan Văn Thắng

- Phan Vũ

- Phan Xine

- Phan Xuân Sinh

- Phannguyên Psg

- Phanxipăng

- Phaolô VI

- phap

- Pháp Hoan

- Pháp Vân

- Phapxa Chan

- Phát biểu nhận giải Văn Việt

- Phi Hà

- Phil Caputo

- Philip Larkin

- Philip Roth

- Phong Âm

- Phong Linh

- Phong Nguyen

- Phong Quang

- Phố Văn

- Phú Quang

- Phù Sa

- Phúc Lai GB

- Phúc Tiến

- Phunchok Stobdan

- Phùng Anh Kiệt

- Phùng Hi

- Phùng Hoài Ngọc

- Phùng Học Vinh

- Phùng Ngọc Kiên

- Phùng Nguyễn

- Phùng Quán

- Phùng Thành Chủng

- Phùng Thị Hạ Nguyên

- Phùng Thị Như Hà

- Phuong Ta

- Phương Chi

- Phương Hương

- Phương Phương

- Phương Thảo

- Phương Thuý

- Phương Uy

- Phương Xích Lô

- Pierre Bayard

- Pierre Darriulat

- Pierre Lemieux

- Prashanth Parameswaran

- Qladimir Pyljow

- Quách Cường

- Quách Hạo Nhiên

- Quách Tấn

- Quách Thoại

- Quảng Diệu Trần Bảo Toàn

- Quang Dũng

- Quang Đức

- Quang Minh

- Quang Phan

- Quảng Tánh Trần Cầm

- Quậy Nguyễn

- Quế Hương

- Quốc Dũng

- Quốc Phương

- Quốc Toản

- Quyên Di

- Quyên Hoàng

- Quỳnh Dao

- Quỳnh Hợp

- Quỳnh Iris de Prelle

- Quỳnh Vi

- Rabindranath Tagore

- Rachel Adams

- Rainer Maria Rilke

- Ralph Chaplin

- Rebecca Mead

- Rebecca Solnit

- Reiner Traub

- Remo Verdickt

- Riccardo Gazzaniga

- Richard C. Paddock

- Richard Millet

- Richard Serra

- Richard Seymur

- Robert Desnos

- Robert McCrump

- Roger Vu

- Roger-Pol Droit

- Roland Barthes

- Romain Rolland

- Ronald F. Inglehart

- Rory O’Sullivan

- Ruben David Gonzalez Gallego

- Russell Edson

- Ruth Ingram

- Ryszard Legutko

- Saint-John Perse

- Salman Rushdie

- Salvatore Babones

- Sam Dresser

- Sạn chữ

- San Phi

- Sandra Kerschbaumer

- Sara Teasdale

- Sarah Pulliam Bailey

- Sarah Thornton

- Sáu Nghệ

- Sergio Bitar

- Shaimaa El Sabbagh

- Shakespeare

- Shannon Van Sant

- Sheikha A

- Sheila Fischman

- Sheila Ngoc Pham

- Sheri Berman

- Shigeeda Yutaka

- Shirin Ebadi

- Shukshin

- Simon Johnson

- Sire Apm Lukwesa

- Slavoj Žižek

- Sohaniim

- Son Kieu Mai

- Song Chi

- Song Hà

- Song Nguyễn

- Song Phạm

- Song Phan

- Song Thao

- Sophie Trịnh

- Số đặc biệt

- Sơn Ca

- Sơn Hoàng Liên

- Sơn Kiều Mai

- Sơn Nam

- Stalin

- Stefan Dege

- Stefano Harney

- Stephan Koester

- Stephen B. Young

- Steve Earle

- Susan Sontag

- Suzuki Katsuhiko

- Sương Nguyệt Minh

- Sương Quỳnh

- Svetlana Alexievich

- Svetlana Alexievitch

- Svetlana Alexiévitch

- Sylvia Plath

- T. Đ.

- T.Vấn

- Tạ Anh Thư

- Tạ Chí Đại Trường

- Tạ Duy Anh

- Tạ Tỵ

- Tạ Văn Tài

- Tạ Văn Thông

- Tạ Xuân Hải

- Tadeusz Rósewicz

- Tam Ích

- Tamarchenko

- Tàn Tuyết

- Tanaami Keiichi

- Taras Shevchenko

- Tarik Khaldi

- Tawada Yoko

- Tawfiq Zayyad

- Tăng Quang

- Tâm An

- Tâm Bình

- Tâm Chánh

- Tâm Don

- Tâm Thường Định

- Tâm Việt

- Tấn An

- Teolinda Gersão

- Teresa Mỹ Chúc

- Thạch Đạt Lang

- Thạch Quỳ

- Thạch Thảo

- Thái Bá Tân

- Thái Bá Vân

- Thái Bảo

- Thái Hà

- Thái Hạo

- Thái Kế Toại

- Thái Kim Lan

- Thái Mai Lan

- Thái Ngọc San

- Thái Phan Vàng Anh

- Thái Sinh

- Thái Thanh

- Thái Thanh Sơn

- Thái Thăng Long

- Thái Tuấn

- Thái Văn

- Thái Văn Đào

- Thái Vũ

- Thanh Chung

- Thạnh Đà

- Thanh Hằng

- Thanh Hằng - Anh Khoa

- Thành Lộc

- Thanh Nam

- Thanh Ngọc

- Thanh Phương

- Thanh Tâm Tuyền

- Thanh Thảo

- Thanh Thuỷ

- Thanh Trúc

- Thanh Tùng

- Thanh Xuân

- Thanhhà Lại

- Thảo Dân

- Thao Dinh

- Thảo luận

- Thảo Nguyên

- Thảo Trường

- Thảo Vy

- Thẩm Đống

- Thẩm Hoàng Long

- Thận Nhiên

- Thân Trọng Mẫn

- Thân Trọng Sơn

- Thế Dũng

- Thế Giang

- Thế Quân

- THẾ THANH

- Thế Uyên

- Thi Hoàng

- Thi Nguyên

- Thi sỹ ỦA

- Thi Vũ

- Thích Nhất Hạnh

- Thích Nữ Chân Không

- Thích Phước An

- Thích Quảng Độ

- Thierry Leclère

- Thierry Lentz

- Thiên Di

- Thiên Điểu

- Thiền Lâm

- Thiền Nguyễn

- Thiên Thai

- Thiện Tùng

- Thiện Ý

- Thiền Zen Paul Vân Thuyết

- Thiết Thạch

- Thiếu Khanh

- Thiều Mai Lâm

- Tho Nguyen

- Thọ Nguyễn

- Thomas A. Bass

- Thomas Bo Pedersen

- Thomas Mahler

- Thomas S. Mullaney

- Thông Đặng

- Thơ

- Thơ Marie Howe

- Thụ Nguyên

- Thu Phong

- Thu Vàng

- Thuận

- Thuần Ngô

- Thuận Paris

- Thuận Thiên

- Thục Quyên

- Thụy An

- Thùy Dung

- Thụy Khuê

- Thùy Linh

- Thụy My

- Thủy Tiên

- Thư Bạn Đọc

- Thường Quán

- Thy An

- Tịch Ru

- Tiet Hung Thai

- Tiền Giang

- Tiêu Dao Bảo Cự

- Tiêu Kiện Sinh

- Tiêu Toàn

- Tiểu Tử

- Tiểu Vũ

- Tillman Miller

- Timothy Brennan

- Timothy Garton Ash

- Timothy Snyder

- Tina Hà Giang

- Tino Cao

- Tobi Trần

- Tom Fawthrop

- Tomas Tranströmer

- Tô Đăng Khoa

- Tô Hải

- Tô Hoàng

- Tố Hữu

- Tô Lan Hương

- Tô Ngọc Vân

- Tô Thẩm Huy

- Tô Thùy Yên

- Tô Văn Trường

- Tôi Đây

- Tôn Thất Thông

- Tôn Thất Tùng

- Tống Văn Công

- Trà Bình

- Trà Đóa

- Trà Nhiên

- Tracy K. Smith

- Tran Dinh Dung

- Tran Nam Dung

- Trang Châu

- Trang Hạ

- Trang Thanh

- Trang Thế Hy

- Trangđài Glassey Trầnguyễn

- Trangđài Glasssey-Trầnguyễn

- Trao đổi

- Trầm Tử Thiêng

- Trần Anh Hùng

- Trần Bá Đại Dương

- Trần Bang

- Trần Bình Nam

- Trần C. Trí

- Trần Cao Lĩnh

- Trần Cao Tường

- Trần Công Tâm

- Trần Công Tín

- Trần Dạ Từ

- Trần Dần

- Trần Doãn Nho

- Trần Dũng Thanh Huy

- Trần Duy

- Trần Duy Phiên

- Trần Duy Trung

- Trần Đăng Khoa

- Trần Đăng Tuấn

- Trần Đĩnh

- Trần Đình Bút

- Trần Đình Hoành

- Trần Đình Lương

- Trần Đình Sơn Cước

- Trần Đình Sử

- Trần Đình Thắng

- Trần Đình Triển

- Trần Đình Trợ

- Trần Độ

- Trần Đồng Minh

- Trần Đức Anh Sơn

- Trần Đức Nguyên

- Trần Đức Thảo

- Trần Đức Tiến

- Trần Đức Tín

- Trần Đức Toản

- Trần Gia Huấn

- Trần Gia Ninh

- Trần Hà Linh

- Trần Hạ Tháp

- Trần Hạ Vi

- Trần Hải

- Trần Hạnh

- Trần Hậu

- Trần Hoài Anh

- Trần Hoài Thư

- Trần Hoàng Phố

- Trần Hoàng Trúc

- Trần Hoàng Vy

- Trần Hùng

- Trần Huy Bích

- Trần Huy Mẫn

- Trần Huy Minh Phương

- Trần Huy Quang

- Trần Huyền Sâm

- Trần Huỳnh Duy Thức

- Trần Hữu Dũng

- Trần Hữu Khánh

- Trần Hữu Quang

- Trần Hữu Tá

- Trần Hữu Thục

- Trần Khánh Triệu

- Trần Kiêm Đoàn

- Trần Kiêm Trinh Tiên

- Trần Kim Trắc

- Trần Kỳ Trung

- Trần Lam

- Trần Lê Hoa Tranh

- Trần Lê Sơn Ý

- Trần Lương

- Trần Lý Trí Tân

- Trần Mạnh Hảo

- Trần Mạnh Tuấn

- Trần Minh Phi

- Trần Minh Quốc

- Trần Mộng Tú

- Trần Nam Anh

- Trần Nam Bình

- Trần Ngân Hà

- Trần Nghi Hoàng

- Trần Ngọc Cư

- Trần Ngọc Hiếu

- Trần Ngọc Tuấn

- Trần Ngọc Vương

- Trần Nguyên Đán

- Trần Nhã Thụy

- Trần Nhương

- Trần Phong Giao

- Trần Phong Vũ

- Trần Quang Đức

- Trần Quang Lộc

- Trần Quốc Anh

- Trần Quốc Nam

- Trần Quốc Thuận

- Trần Quốc Toàn

- Trần Quốc Trọng

- Trần Quốc Vượng

- Trần Quyết Thắng

- Trân Sa

- Trần Song Hào

- Trần Thành

- Trần Thanh Ái

- Trần Thanh Cảnh

- Trần Thanh Huy

- Trần Thanh Vân

- Trần Thắng

- Trần Thế Vĩnh

- Trần Thị Băng Thanh

- Trần Thị Diệu Tâm

- Trần Thị Lai Hồng

- Trần Thị Lam

- Trần Thị NgH.

- Trần Thị Nguyệt Mai

- Trần Thị Phương Phương

- Trần Thị Thanh Thoả

- Trần Thị Thu Hoài

- Trần Thị Trường

- Trần Thiện Đạo

- Trần Thùy Mai

- Trần Tiến

- Trần Tiễn Cao Đăng

- Trần Tiến Dũng

- Trần Tiễn Khanh

- Trần Tố Nga

- Trần Trọng Dương

- Trần Trọng Thức

- Trần Trọng Vũ

- Trần Trung Chính

- Trần Trung Đạo

- Trần Tuấn

- Trần Từ Mai

- Trần Vàng Sao

- Trần Văn Chánh

- Trần Văn Chung

- Trần Văn Đỉnh

- Trần Văn Khê

- Trần Văn Minh

- Trần Văn Nam

- Trần Văn Thọ

- Trần Văn Thủy

- Trần Văn Tý

- Trần Vấn Lệ

- Trần Việt Hà

- Trần Viết Ngạc

- Trần Vinh Dự

- Trần Vũ

- Trần Vũ Hải

- Trần Vương Thuấn

- Trần Vương Thuận

- Trần Wũ Khang

- Trần Xuân Hoài

- Trần Xuân Kiêm

- Trần Xuân Linh

- Trần Xuân Lĩnh

- Trần Xuân Thảo

- Trần Ý Dịu

- Trần Yên Hòa

- Trần Yên Nguyên

- Trên

- Trên Facebook

- Trên Facebook/Minds

- Trên kệ sách

- Trên trang diaCRITICS

- Trí Hiệu Dân

- Triều Anh

- Triều Hoa Đại

- Triêu Nhan

- Triều Sơn

- Triệu Tử Dương

- Trịnh Anh Tuấn

- Trịnh Bá Phương

- Trịnh Bách

- Trịnh Cao Hòa Thanh

- Trịnh Chu

- Trịnh Công Sơn

- Trịnh Cung

- Trịnh Duy Kỳ

- Trịnh Hữu Long

- Trịnh Kim Tiến

- Trịnh Lữ

- Trịnh Minh Tuấn

- Trịnh Sơn

- Trịnh Thanh Thủy

- Trịnh Thu Tuyết

- Trịnh Vĩnh Phúc

- Trịnh Xuân Thuận

- Trịnh Xuân Thủy

- Trịnh Y Thư

- Trọng Anh

- Trọng Phú

- Trọng Thành

- Tru Sa

- Trúc Giang

- Trúc Thông

- Trúc Ty

- Trump

- Trung Bảo

- Trung Dũng Kqd

- Trung Dũng Kqđ

- Trùng Dương

- Trung Đào

- Trung Trung Đỉnh

- Trư Sa

- Trường An

- Trương Anh Ngọc

- Trương Anh Thụy

- Trương Chính

- Trương Duy Nhất

- Trương Đăng Dung

- Trương Điện Thắng

- Trương Đình Phượng

- Trương Hồng Quang

- Trương Huy San

- Trường Minh

- Trương Ngọc Chương

- Trương Nguyên

- Trương Nguyện Thành

- Trương Nhân Tuấn

- Trương Phượng

- Trương Quang

- Trương Quang Đệ

- Trương Quang Nhuệ

- Trương Quang Vĩnh

- Trương Thanh Thuận

- Trương Thị An Na

- Trương Thị Ngọc Hân

- Trương Thiên Phàm

- Trương Thu Hiền

- Trương Tố Hoa

- Trương Trọng Nghĩa

- Trương Tửu

- Trương Văn Dân

- Trương Văn Vĩnh

- Trương Vũ

- Trương Xuân Thiên

- Tú Mỡ

- Tù Quốc Hoài

- Tù Sâm

- Tú Trung Hồ

- Tuấn Duy

- Tuấn Khanh

- Tuân Nguyễn

- Tuấn Thảo

- Tuệ Anh

- Tuệ Đăng

- Tuệ Nguyên

- Tuệ Nhân

- Tuệ Nhật

- Tuệ Sĩ

- Tuệ Sỹ

- Tùng Dương Cola

- Tung Nguyen

- Turner

- Túy Hồng

- Tuyết Nghi

- Tư

- Từ Dung

- Tư liệu

- Tử Linh

- Từ Mai Trần Huy Bích

- Từ Quốc Hoài

- Từ Sâm

- Từ Thức

- Tưởng

- Tương Lai

- Uejima Onitsura

- Umberto Eco

- Uông Tăng Kỳ

- Uông Triều

- Uyển Ca

- Uyên Nguyên

- Uyên Nguyễn

- Uyên Thao

- Uyên Vũ

- V. Erofiev

- Václav Havel

- Vàng A Giang

- Varlam Shalamov

- Vasco Gargalo

- Vasily Makarovich

- Vasyl Stus

- Văn

- Văn Biển

- Văn Cao

- Văn Chinh

- Văn Công Hùng

- Văn Giá

- Văn học

- Văn học Miền Nam 54-75

- Văn Như Cương

- Văn Quang

- Văn Tâm

- Văn Văn Của

- Văn Việt

- Văn;

- Văn.

- Vấn đề hôm nay

- Vận Động Ứng Cử Đại Biểu Quốc Hội 2016

- Vân Hạ

- Vân Phi

- Velcrow Ripper

- Veronica Melkozerova

- Vi Lãng

- Vi Trần

- Vi Yên

- Viet Thanh Nguyen

- Viên Linh

- Việt Bách

- Việt Bình

- Việt Dzũng

- Việt Khang

- Việt Lang

- Việt Phương

- Viktor Astafyev

- Viktor Maslov

- Vinh Anh

- Vĩnh Điện

- Vĩnh Hảo

- Vĩnh Quyền

- Virginia Heffernan

- Virginia Woolf

- Vladimir Nabokov

- Vladimir Voronov

- Võ An Đôn

- Võ Anh Minh

- Võ Anh Thơ

- Võ Bá Cường

- Võ Đắc Danh

- Võ Định Hình

- Võ Đức Phúc

- Võ Hồng

- Võ Huy Tâm

- Võ Hương Quỳnh

- Võ Kỳ Điền

- Võ Ngàn Sông

- Võ Phiến

- Võ Thị Hảo

- Võ Thị Thu Hằng

- Võ Tiến Cường

- Võ Tòng Xuân

- Võ Trí Hảo

- Võ Văn Quản

- Võ Văn Tạo

- Võ Văn Thôn

- Võ Xuân Quế

- Võ Xuân Sơn

- Volker Weidermann

- Volodymyr Vynnychenko

- Volodymyr Zelenskyy

- Vũ

- Vũ Bằng

- Vũ Biện Điền

- Vũ Cao Đàm

- Vũ Cát Tường

- Vũ Đình Hòe

- Vũ Đình Huỳnh

- Vũ Đình Liên

- Vũ Đình Phòng

- Vũ Đức Khanh

- Vũ Đức Phúc

- Vũ Đức Sao Biển

- Vu Gia

- Vũ Hà Văn

- Vũ Hạnh

- Vũ Hoàng Chương

- Vũ Hoàng Thư

- Vũ Hồng Ánh

- Vũ Huy Ngọc

- Vũ Huy Quang

- Vũ Khắc Hoè

- Vũ Khắc Khoan

- Vũ Kim Hạnh

- Vũ Kim Thu

- Vũ Lâm

- Vũ Lập Nhật

- Vũ My Lan

- Vũ Ngọc Giao

- Vũ Ngọc Hoàng

- Vũ Ngọc Tâm

- Vũ Ngọc Tiến

- Vũ Nho

- Vũ Oanh

- Vũ Quang Việt

- Vũ Quí Hạo Nhiên

- Vũ Quốc Ngữ

- Vũ Quỳnh Hương

- Vũ Quỳnh Nh.

- Vũ Thành Sơn

- Vũ Thanh Tâm

- Vũ Thanh Tùng

- Vũ Thành Tự Anh

- Vũ Thế Khôi

- Vũ Thị Hải

- Vũ Thị Nhuận

- Vũ Thị Phương Anh

- Vũ Thị Phương Lan

- Vũ Thị Thanh

- Vũ Thị Thanh Mai

- Vũ Thư Hiên

- Vũ Tiến Lập

- Vũ Trọng Khải

- Vũ Trọng Phụng

- Vũ Tuấn Hoàng

- Vũ Từ Trang

- Vũ Tường

- Vũ Viết Tuân

- Vũ Xuân Tửu

- Vương Bích Ngọc

- Vương Đan

- Vương Hỗ Ninh

- Vương Huy

- Vương Ngọc Minh

- Vương Tiểu Nhị

- Vương Trí Nhàn

- Vương Trọng

- Vương Trùng Dương

- Vương Trung Hiếu

- Vy Thảo

- W. H. Auden

- Wa Praong

- Walt Whitman

- Walter Isaacson

- Wayne Karlin

- Wells

- Wendy Barker

- Wiesiek Powaga

- Wilhelm Schmid

- Will Nguyen

- William Carlos Williams

- William Nee

- William Stafford

- William Stanley Merwin

- Winston Phan Đào Nguyên

- Wislawa Szymborska

- Władysław Reymont

- Wolf Biermann

- Wolfgang Borchert

- Wynn Gadkar Wilcox

- Xì Trum

- Xie Tao

- Xuân Ba

- Xuân Diệu

- Xuân Dương

- Xuân Đài

- Xuân Minh

- Xuân Phượng

- Xuân Sách

- Xuân Thọ

- Xuân Vũ

- Xương Văn

- Y Chan

- Ỷ Lan

- Ý Nhi

- Y Uyên

- Yanis Varoufakis

- Yasmine M’Barek

- Yevgeny Yevtushenko

- Yên Ba

- Yên Khắc Chính

- Yến Năng

- Yên San

- Yên San Thụy Miên

- Yên Thao

- Yiyun Li

- Yoko Ogawa

- Yōko Ogawa

- Yoko Tawada

- Yosano Akiko

- Young Sang Lee

- Yuliya Ilchuk

- Yuno Bigboi

- Yves Sintomer

- Yvette Tan

- Zac Herman

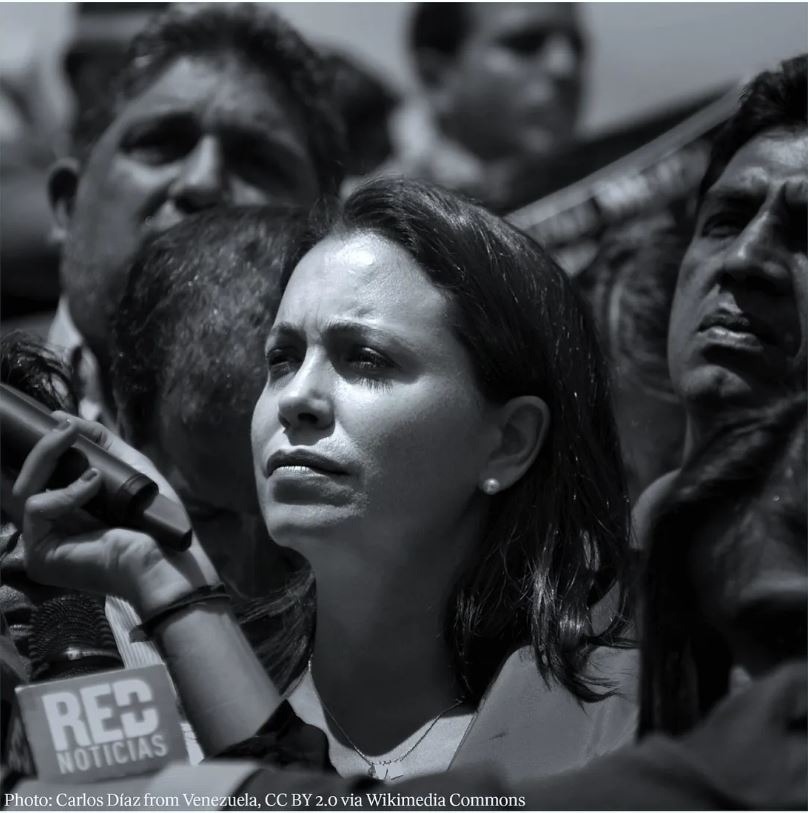

María Corina Machado – Người đàn bà không chịu câm lặng

Tino Cao